By Jay Kuehner, independent film critic and educator

Looking at Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s 1932 photograph Las lavanderas sobreentendidas (The Washerwomen Implied) in a preview of the Luces y Sombras exhibit, I was taken by its discreet but uncanny composition: linens draped on the blades of large maguey plants, foregrounded in a patch of white clouds seemingly respired in the sky behind. While too haphazard to be so iconic, too muted to be maximally symbolic, and certainly not discreet in title, the image nevertheless bloomed, despite or on account of its minimalism, into my consciousness. The delicate covering conveys something elegiac – has something or someone here passed on? – while the spiky pencas thrust violently upward toward an oblivion of sky. Is it the soft linen that makes the plant seem, by contrast, belligerent? The poise with which the two elements apparently accommodate each other suggests some syncretic instance of nature and civilization working in jagged harmony.

In reality it’s just the laundry hung out to dry, from which Álvarez Bravo has not so much crafted something mythic as yielded to it, disclosed through the simplest of glances. But the real ‘subject’ of the photograph is that which is unseen, out of frame, and, as per that ironically determinate title, implied. The washerwomen. They who can not be seen but are ineluctably inferred. Their absence becomes, in the photograph, a presence. Between the thread of linen and the succulent’s armor ushers the sentient skin of the hand, imagined. What could reveal these lavanderas, other than Álvarez Bravo training his camera otherwise directly upon them? If the frame remained static, perhaps the temporal image could tell us more of their coming and going, their labor now causally conjoined to its source material. The women and their endeavors might thus become visible, although perhaps no more powerfully so. But it might give us an accounting of certain fates, however ephemeral. What was latent becomes supple.

This temporal element, intrinsic to film and video, became the genesis of Rayos, with its capacity to act in dialogue with the spaces opened up in Luces y Sombras’ implied histories. A survey of cinema (here loosely defined as the art of the moving image, of both raw film stock and the subsequent advent of the digital pixel) within Mexico could not act as a pure correlative to Luces’ voluminous effect (among which several more beguiling Alvarez Bravo photographs could be seen), but it could function with an adjacent purpose. If there was a film that fleshed out, or even contoured, some of the resonant voids left in Álvarez Bravo’s keen vision of negative space, it might be Eugenio Polgovsky’s Trópico de Cáncer (so named for the film’s latitude), in which the work of multi-generation families subsisting in the arid desert of San Luis Potosi is made visible in the director’s dogged pursuit (with a dusty-lensed digital video camera) of their primitive hunt-and-gather excursions. Here, the women’s labor is not implied, but rather carried out in full view of an inhospitable roadside where they sell their wares – sun dried snake skins and boxed birds – to passing truckers and curious tourists.

1.

While not without its own ellipses and aesthetic elisions, the film offers a candid and raw portrait of survival and resilience; not as a poetically symbolic gesture of mexicanidad, but as a lived social reality – from which Polgovsky salvages something lyrical nonetheless. The work of photographer Pablo Ortíz Monasterio is not included in the Luces y Sombras exhibit, but I’m reminded of a gesture – the return of the subject’s gaze prevalent in his photos – in which one young hunter in Trópico who, rather efficiently picking off his prey in the cacti with a slingshot, proceeds to turn his homemade weapon toward the camera, and by implication the audience. It’s a playful yet tense moment, a confrontation between director and subject, and by extension the dialectics of city and country, machine and nature, that constitute the operational framework of Polgovsky’s film. Scholar Ximena Keogh Serrano, who spoke post-screening about the film’s myriad registers, also framed this along an axis of indigenous/colonial legacies. In other words, the persistently problematic issue of representation as a corporeal, social, technological, and national phenomenon, to which Polgovsky appears carefully attuned but is implicated within. It is by virtue of a certain unassuming presence, and unseen hand, that the photographer and director as well become sobreentendidos in the very scenes they depict, but this stance of the innocent interlocutor of reality may be yet another abiding myth of modernism.

__

The Lumières are often credited with the invention of modern cinema, their La Sortie des ouvriers de l’usine Lumière (“Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory”, 1895) cited as the primal reel that got the seventh art off the ground. But rarely do we imagine the image of Porfirio Díaz, military general and then president of México, astride a horse in Chapultepec park, filmed in 1896 by a team promoting the Lumières’ cinematographe. Thus begins a history of Cine en México, a fraught and fantastic centennial journey that could take a lifetime to truly discover, and to which one could devote an entire season of melodramas from the Golden Age by Roberto Gavaldón and Emilio Fernández. But it seemed fitting to have commenced the series with a film whose production speaks directly to the industry’s situation in the 1930s at the intersection of art, politics, foreign influence, and working people. That film is Redes, often translated into English as “Waves” but literally meaning “Nets”, itself the source of sustenance for an entire fishing village in Veracruz.

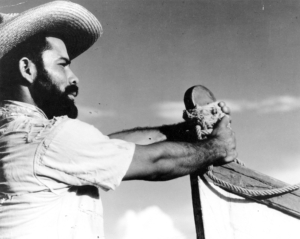

The thought of a state-sponsored docu-fiction extolling the virtues of solidarity in labor, circa 1936 in Mexico, shot by an American avant-garde photographer and co-directed by an expatriate Austrian and a Mexican national, seems unfathomable in hindsight. Yet this was precisely the case with Redes, its storied production often eclipsing the narrative on-screen. Nearly a century on, the film’s improbable conception has faded to reveal a masterpiece that, in spite of countervailing creative forces, would anticipate social realism in cinema and usher in an unprecedented era of filmmaking in Mexico (the auspicious “Cine de oro”) that would endure for three decades. It would also announce the careers of Paul Strand, Fred Zinneman, and Emilio Gómez Muriel to world audiences, their ensuing work practically defining their respective mediums of photography and film.

The film was conceived under the auspices of an emergent socialist education agenda, for which composer Carlos Chávez was appointed. It was Strand and Agustín Velásquez Chávez, nephew to Carlos, who had been tasked to write scenarios for what was then a proposed documentary about the ill-treatment of poor fishermen in Alvarado in the state of Veracruz (originally entitled Pescados). Henwar Rodakiewicz, a friend of Strand’s from New York (and director of the documentary Portrait of a Young Man), was enlisted to assist with script and direction, but would soon invite Fred Zinneman (who had collaborated in Germany with Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, and Billy Wilder on the silent documentary-inflected drama People on Sunday) to fill his shoes. Neither Strand nor Zinneman were Spanish speakers, so Emilio Gómez Muriel, himself recently returned from a stint in Hollywood and originally hired as line producer, became co-director – no doubt taking the lead with the mostly non-professional cast of locals.

2.

According to Charles Ramírez Berg (professor of film studies at the University of Texas at Austin) the notoriously ill-fated shoot owed considerably to the tension between Strand and Zinneman’s conflicting aesthetics (which the final film radically synthesized with its bold static compositions favored by Strand and the perpetual movement of action preferred by Zinneman). Shooting on location in a hot fishing village, often without electricity, and using a hand-cracked camera would take a cumulative toll on the production; what critic Kent Jones described as “acrimony and disillusionment”. Both time and money were running out, and exposed footage required processing in Los Angeles, to which sound was later added (as well as a brilliant score by a renown composer other than Chávez, Silvestre Revueltas).

Given the circumstances, it seems miraculous that the film was finished at all. In spite of the internal drama of its making, the film has aged with an almost uncanny prescience, owing to its committed socially-conscious politics and acute observation of labor. Its real miracle is the collective effort and dramatic effect of the local, non-professional cast, lending the film an authenticity that would prefigure Visconti’s La Terra Trema (a neorealist depiction of struggling Sicilian fishermen, 1942), and thus an insistence upon the real within fictional portraits on film. Scenes of fishermen in pursuit of their catch, rowing on open seas, are among the most mesmeric in early cinema history, and the alternately abstract and near-palpable presentation of the fish – netted, handled, traded at market – suggests a perspective beyond the anthropos. Though in the end the film is positively human in its narrative arc, while being decidedly propagandistic, it is the melancholy of martyrdom and the entropy of rebellion that clearly favor drama above the documentary impulse. For an ostensibly educational film weighted with the utopian ambitions of its time and milieu, Redes has certainly transcended its fraught origin stories to become a singular object of beauty in the history of Mexican, and for that matter global, cinema.

__

It was incidental, but perhaps inevitable, that Rayos would cede to the centripetal pull of the capital, in which CDMX (formerly known as D.F.) features prominently on screen, and scarcely as a backdrop but rather an entropic loci of what authors and chilangos Carlos Monsiváis and Juan Villoro alternately refer to as Los rituales del caos and horizontal vertigo. Sorry, no Roma here (with all due respect to Alfonso Cuarón’s nostalgic ode to domestic labor, though Lila Avilés’ La camarista (The Chambermaid) speaks more eloquently to that). Centro, and specifically the Zócalo, get heady exposure in Rayos, for reasons mostly tragic but, this being Mexico City, with improbable levity too. It was Villoro who situated the capital as existing perpetually “between carnival and drama” and where “partying combines with catastrophe”. Indeed this is the very essence of Polgovsky’s Mitote (which was somewhat lazily translated in English as “Mexican Ritual” but means “celebration” in ancient Nahuatl; mitotia being “to make dances”).

3.

Implicit in Polgovsky’s conception of the central square is its foundation a result of destruction to the natural environment as well as obliteration of native peoples (amid the chaos of the square Polgovsky often cuts to the remnants of the Aztec Empire within the Templo Mayor). Above ground too there are the modern day ‘shamans’ dressed in pre-Columbian garb performing spiritual cleansing rituals for bemused onlookers. Disclosed in the peripatetic gaze of the camera slinking through crowds is a kind of urban ethnology among the striking electrical workers, World Cup revelers cheering on El tri, repenters, and those mercurial entrepreneurs who alight on the square to convert most anything into a sale. There is no grand takeaway or moral message to Polgovsky’s teeming portrait, beyond Villoro’s definition of Mexico City as simply “too many people”, albeit not a single one superfluous.

This enigma gets at the heart, or pit, of Juan Carlos Rulfo’s En el hoyo, his extraordinary 2006 documentary about labor in extremis, as a crew of construction workers is seen laboring intensively on the newly commissioned second tier of the Anillo Periférico freeway that circumscribes the city. As a crucible in which the city’s future transport system is forged (one from which, it should be noted, many of these workers will largely be excluded), the pit of concrete, steel, and dirt is revealed as a kind of social and economic sanctuary, and conversely a graveyard. Their labor is mostly invisible if not unappreciated by the thousands of drivers who skirt the site daily, and Rulfo takes the opportunity to listen, and watch, as they emerge as full fledged characters in this seemingly infinite drama. Cutaways reveal quotidian and ritual moments of home life for these workers, often in rural habitats, far from the din and dust of the pit. Theirs is not a mythologically proportioned effort, but Rulfo intimates a dignified element (barring the misogynistic catcalls) to their labor while himself rigged to the pillars of rebar with his hand-held digital camera.

4.

More clandestine yet no less courageous are the shots recorded by the young student activist and cineasta Leobardo López Aretche from the trunk of a car as the city is engulfed in protest in El Grito, a landmark documentary that was suppressed by the government for decades since its almost impossible conception as a collective student work. Unrest in the city mounted throughout the summer as social inequalities were brought to light amid a promoted civic image as México hosted the ‘68 Olympics. The military brutality culminated in the massacre at Tlatelolco, still remembered today, and López Aretche’s document stands as a celluloid in situ memorial to the atrocity, not least in its portrayal of youth less at war but in moments of typical repose: flirting, hanging out, and quipping – until the situation grew horribly dark.

5.

The collective ‘cry’ of the title echoes in multivalent ways in the city center still, elegy merging with the whisper of prayer, the clap of thunder, the vendor’s bellow, and alas cries of joy in sound artist Félix Blume’s “Los Gritos de México”, a sonic tapestry that captures a sonorous portrait of the feverish metropolis in its fifth century ever unasleep. The spirit of Blume’s city symphony finds coincidental expression in the series’ final title, an expansively imagined micro-portrait of the city shot by cinematographers Lisa Tillinger and Gerardo Barroso, Calle López. The eponymous downtown street becomes host to a series of minutely observed gestures that blossom into epiphanies under the carefully composed, inky black-and-white photography of the directors’ patient and loving gaze. They defer to their subjects as ultimately inscrutable, yet all too relatable in their daily rounds of work (and very occasional rest), in song and story. Taquero, butcher, juicer, lavadera de autos, kiosk vendor (with child in constant tow) all populate this sumptuous choreography of daily life, lending the street a vitality that feels palpably faithful to the act of being there, subject implied and acknowledged. It’s a fitting tribute to the host of images made in México that Rayos has celebrated these last several months, amulets of light for times of carnival and catastrophe.

- Image courtesy of Tecolote Films

- Image courtesy of Cineteca Nacional

- Image courtesy of Tecolote Films

- Image courtesy of Juan Carlos Rulfo

- Image courtesy of Cineteca Nacional