Notes on Redes (1936)

The Lumières are often credited with the invention of modern cinema, their La Sortie des ouvriers de l’usine Lumière (“Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory”, 1895) often cited as the primal reel that got the seventh art off the ground. But rarely do we imagine the image of Porfirio Díaz, military general and then president, astride a horse in Chapultepec park, filmed in 1896 by a team promoting the Lumières’ cinematographe. Thus begins a history of Cine en México, a fraught and fantastic centennial journey that could take a lifetime to truly discover. Can the story be distilled down to a handful of formative films? Certainly not, and one could devote an entire season to melodramas from the Golden Age by Roberto Gavaldón and Emilio Fernández. But it seemed fitting to begin with a film whose production speaks volumes to the industry’s situation in the 1930s at the intersection of art, politics, foreign influence, and working people. That film is Redes, often translated into English as “Waves” but literally meaning “Nets”, the primary material source of sustenance for an entire fishing village in Veracruz.

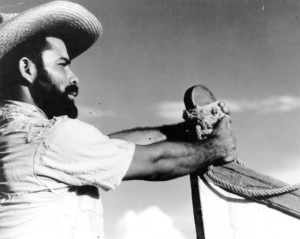

The thought of a state-sponsored docu-fiction extolling the virtues of solidarity in labor, circa 1936 in Mexico, shot by an American avant-garde photographer and co-directed by an expatriate Austrian and a Mexican national, seems unfathomable in hindsight. Yet this was precisely the case with Redes, a film whose ambitiously troubled production often eclipsed the final product. Nearly a century on, the film’s improbable conception has faded to reveal a masterpiece that, in spite of countervailing creative forces, would augur social realism in cinema and usher in an unprecedented era of filmmaking in Mexico (the auspicious “Cine de oro”) that would endure for three decades. It would also announce the careers of Paul Strand, Fred Zinneman, and Emilio Gómez Muriel to world audiences, their ensuing work practically defining their respective mediums of photography and film.

The film was conceived under the auspices of an emergent socialist education agenda, for which composer Carlos Chávez was appointed. It was Strand and Agustín Velásquez Chávez, nephew to Carlos, who had been tasked to write scenarios for what was then a proposed documentary about the ill-treatment of poor fishermen in Alvarado in the state of Veracruz (originally entitled Pescados). Henwar Rodakiewicz, a friend of Strand’s from New York (and director of the documentary Portrait of a Young Man), was enlisted to assist with script and direction, but would soon invite Fred Zinneman (who had collaborated in Germany with Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, and Billy Wilder on the silent documentary-inflected drama People on Sunday) to fill his shoes. Neither Strand nor Zinneman were Spanish speakers, so Emilio Gómez Muriel, himself recently returned from a stint in Hollywood and originally hired as line producer, became co-director – no doubt taking the lead with the mostly non-professional cast of locals.

According to Charles Ramírez Berg (professor of film studies at the University of Texas at Austin) the notoriously ill-fated shoot owed considerably to the tension between Strand and Zinneman’s conflicting aesthetics (which the final film radically synthesized with its bold static compositions favored by Strand and the perpetual movement of action preferred by Zinneman). Shooting on location in a hot fishing village, often without electricity, and using a hand-cracked camera would take a cumulative toll on the production; what critic Kent Jones described as “acrimony and disillusionment”. Both time and money were running out, and exposed footage required processing in Los Angeles, to which sound was later added (as well as a brilliant score by a renown composer other than Chávez, Silvestre Revueltas).

Given the circumstances, it seems miraculous that the film was finished at all. In spite of the internal drama of its making, the film has aged with an almost uncanny prescience, owing to its committed socially-conscious politics and acute observation of labor. Its real miracle is the collective effort and effect of the native cast, lending the film an authenticity that would prefigure Visconti’s La Terra Trema (a neorealist depiction of struggling Sicilian fishermen, 1942), and thus an insistence upon the real within fictional portraits on film. Scenes of fishermen in pursuit of their catch, rowing on open seas, are among the most mesmeric in cinema history, and the alternately abstract and near-palpable presentation of the fish – netted, handled, traded at market – suggests a perspective beyond the anthropos. Though in the end the film is positively human in its narrative arc, with the melancholy of martyrdom and the entropy of rebellion clearly favoring drama above the documentary ethos. For an ostensibly educational film weighted with the utopian ambitions of its time and milieu, Redes has certainly transcended its fraught origin stories to become a singular object of beauty in the history of Mexican, and for that matter global, cinema. buena proyección!

Rayos: Cine en México is curated by film programmer David Dinnell and independent film critic and educator Jay Kuehner. Text contributions for Rayos courtesy of Jay Kuehner.