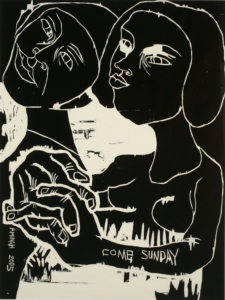

An artist that I have truly come to admire and study is Aminah Robinson. I came across Robinson’s works last year and have been moved by her process and purpose since. I even selected her work, Come Sunday, from TAM’s collection to be included in our current exhibition South Sound Selects: Community Choices from the Collection.

Robinson’s artistry is grounded in community and themes of what home means to Black people. Her art tells what our communities have endured for centuries. She perfectly weaves the histories and stories of everyday people and the communities she’s lived in into her works. It’s inspiring, to say the least.

Robinson was a lifelong resident of Columbus, Ohio; Poindexter Village to be precise. A considerable amount of her work is focused on Columbus while universally speaking to the experience of Black communities throughout the country. She described her works as the “missing pages of American History.” She documented Black traditions and histories and transformed the experiences of everyday people in her communities into her art.

In an interview, Robinson mentions how the elders of her family and community passed down stories. Her father made sure that she spoke with her great aunt, twice a week, every week for 18 years. From taking in and listening to the stories of her elders, she created works that made the history of her communities everlasting.

“She was just a tremendous, beautiful, and kind person who knew how to give me her stories. Even though our Ancestors guide us, they also keep us and give us voice so that we can pass it on. And I guess that is the purpose of my work. Simply to pass it on.”

– Aminah Robinson

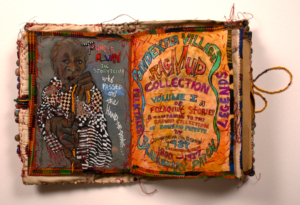

At a young age, her father taught her how to draw and make books from a medium known as hogmawg—homemade paper mixed from glue, mud, twigs, leaves, animal grease, and lime. Her mother taught her weaving, needle, and button work. These materials and techniques are very prominent in her works. You can see them in her two-dimensional and three-dimensional works. Holding on to the styles and techniques passed down to her and making them a prominent part of her artistry speaks to how intimate our traditions are to us. The way she incorporated her own style and folk traditions with her formal learning communicates her reverence for her elders’ and ancestors’ guidance and being grounded in community.

Her desire to understand her roots inspired her to travel to Africa in 1979, where she eventually changed her name from Brenda Lynn to Aminah. This is significant as her travels to Africa introduced her to the Yoruba concept, sankofa. The meaning of sankofa is for one to understand the past in order to truly move forward. You must know where you come from and where you’ve started, so you can move honestly, wholly, and intentionally in the present and future. It’s about being intentional in the way you take and hold the past, and let it guide you. Robinson’s life and artistic process were guided by this concept, and her works were rooted in it.

With the concept of sankofa central to her art, she would constantly revisit and rework her works, which birthed her mixed media works—RagGonNons. The purpose of these was that the art goes on and on and on. They tell the story of what had been taken and lost during slavery. These works were massive as she would continually add to them. Her use of buttons was to trace the journey of souls through various points of Black history, starting from Africa, through enslavement, as well as including a personal family portrait and continuing into the present and future.

Robinson used art as a narrative for her community and the communities she lived in. She was intentional about the purpose of her art. We see this in her style and use of materials to the depictions of people in the communities where she lived. She allowed the stories of her elders and ancestors to guide her.

Art gives a deeper understanding of self and those around you. This is one reason I find art to be transformative and powerful.

Something I think about often is how we, as Black people, choose to keep the memories of our people and our communities alive. I believe Aminah exemplifies this. It’s often said memories and people are not gone until the very last person that holds those memories is no longer with us. Aminah’s art offers immortality to the Black communities she’s lived in and the stories of those everyday people.