In Tacoma Art Museum’s new exhibition Forgotten Stories: Northwest Art of the 1930s, explores how in 1930s the US federal government appreciated art and artists as critical to economic and social recovery. As we navigate through the repercussions of COVID-19, what can we learn from the ideals of the New Deal that can be applied to our current reality and the anticipated challenges for artists and art organizations?

In the wake of the Great Depression, the creation of the New Deal was seen as absolutely essential for getting the nation back on its feet again. The inclusion of the creation of art and support for artists was believed to be as equally fundamental to the recovery as food and shelter. As exhibition curator Margaret Bullock so keenly states in the exhibition catalogue,

“In the midst of a national crisis, the US government gambled on that belief and added the intangible to the practical, fashioning an unprecedented role for the arts in American society.”

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) served not only to employ artists and artisans (over 5,000 at its height), but also fundamentally changed the way the American culture interacted with and thought about art by promoting the development of public art, assisting in the foundation of artists’ careers, and recognizing that the human need to create was valuable and important.

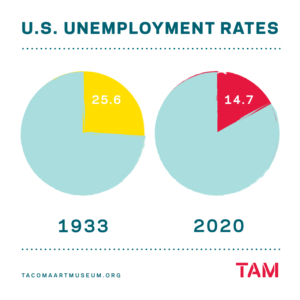

According to Americans for the Arts, each year our country’s 100,000 non-profit arts and culture organizations account for $166.3 billion in total direct expenditures; support 4.6 million jobs; and generate $27.5 billion in revenue for local, state, and federal governments. So with the expected economic losses and dramatic increase in unemployment how will this sector be impacted?

According to Americans for the Arts, each year our country’s 100,000 non-profit arts and culture organizations account for $166.3 billion in total direct expenditures; support 4.6 million jobs; and generate $27.5 billion in revenue for local, state, and federal governments. So with the expected economic losses and dramatic increase in unemployment how will this sector be impacted?

Due to the mass shuttering of theaters, museums, performance halls, and other arts venues, the arts industry quickly started in economic free-fall. Even as staff at these organizations scrambled to shift focus to online content like virtual symphony performances or exhibition tours, arts organizations of all sizes are having to do sweeping and devastating staffing reductions to try to find a way to keep afloat. The Payroll Protection Plan, which provided short-term, forgivable payroll loans to small businesses (including some non-profit organizations), only offered 8-week of payroll coverage.

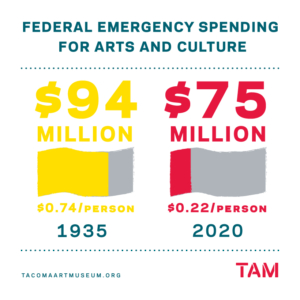

The WPA had a 1935 budget of $1.4 billion dollars per year, which was at that time about 6.7% of the U.S. GDP. The WPA was more than funding for artists. In fact, that was a small part of the overall package, which also supported major construction projects like highways and dams, as well as other significant programs. The Federal Art Project was funded at about $5 million each year.

On March 27, 2020, Congress passed the $2.2 trillion CARES Act bill to provide economic relief for individuals, small business, corporations, state and local governments, education, and public health. Although the Americans for the Arts lobbied for $4 billion to be dedicated to arts and cultural institutions, the final package contained just a sliver of that.

“Arts and culture represent a relatively small part of the $2 trillion-dollar bill compared with the hundreds of billions of dollars for such categories as health care spending and small business loans, but it’s less than what many arts organizations were hoping for. In its recent report, Americans for the Arts called for $4 billion.” Elizabeth Blair, NPR, 3/26/2020.

Artists and arts organizations will mainly benefit from the individual payments and small business relief until the funds run out and it already projected that those dollars will not be enough to meet the needs. In addition to the CARES Act, Congress authorized an additional $75 million for each NEA and NEH and $50 million for IMLS for this year’s budget, or about $200 million. This funding will be distributed by the states adding an additional layer of applications and wait time.

Artists and arts organizations will mainly benefit from the individual payments and small business relief until the funds run out and it already projected that those dollars will not be enough to meet the needs. In addition to the CARES Act, Congress authorized an additional $75 million for each NEA and NEH and $50 million for IMLS for this year’s budget, or about $200 million. This funding will be distributed by the states adding an additional layer of applications and wait time.

One of the underlying themes in Forgotten Stories: Northwest Art of the 1930s is that during this time the federal government, for the first-time, recognized artists as professionals who needed income to continue to work and additionally saw that the power of art could bring communities together, restore hope and help heal a nation which was struggling to pull itself out of the emotional and economic hardships in the wake of The Great Depression.

Those same arguments can be made in even more intense ways now. The economic dominance of the US has shifted to our abilities to be creative and inventive, and away from our manufacturing or agricultural might. The art and cultural sector has been leading the fight to provide arts education which has been stripped from most American schools, and at the same time as fighting to keep doors open and increase access to a wider audience. The future of the recovery of the American economy will lean heavily on our creative resilience to reimagine and create new processes and products.

Artists themselves have been banding together to respond to not only the loss of livelihoods, but also the intense need our society has for humor and hope in this dark time. From drag queens performing live shows, the cast of “Hamilton” sharing a song, or Mo Willems teaching drawing lessons, individuals have risen to the needs and shared their talents and gifts so that the rest of us can feel connected and experience joy.

The recent legislation may be just the beginning of federal assistance to the arts and artists of America. Government leaders have the opportunity to take a minute to reflect on the results and impact of the New Deal on American society, not just the dollar amount, as they find ways to help our cultural and artistic treasures and provide assistance to artists and cultural organizations to survive the coming months and years.

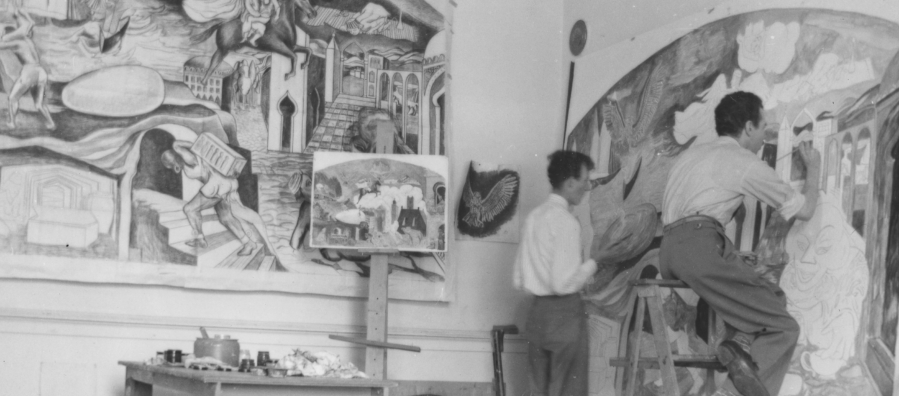

Top image: Artists Louis Bunce and Clifford Gleason painting an Alice in Wonderland mural for Bush Elementary School in Salem, Oregon. Courtesy of the Multanomah County Library.